Some movie theaters get you in the mood for a Hollywood experience. The IFC Center isn’t one of them. It smells musty, looks sticky, and the lights in the bathroom are cold and harsh. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think it had fallen on hard times.

It’s nice enough on the outside, with an old-fashioned marquee that extends over half the sidewalk. To the left of the marquee are two glass façades for coming attractions, a few inches shy of the railing for the West Fourth Street subway stop. To the right, there’s a ticket booth and more cases for posters and merchandise.

If you approach it from West Third Street, you’ll see the marquee first, then the bright posters and silver-rimmed doors. You wouldn’t think the interior is run down, but you might guess that whatever’s inside will be memorable, which is true. It’s a place to be darkly charmed. Eleven years ago, I teared up at a screening of The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. When the lights came on, everyone else was crying too.

I was there the other night for a special event: Crispin Glover’s traveling show. Glover is an actor and filmmaker best known for playing Marty McFly’s dad in Back to the Future. Two years later, he started a company that makes extremely weird films. They have three titles to date: What Is It?; It is Fine! Everything is Fine.; and No! You’re Wrong, or: Spooky Action at a Distance, which was released earlier this month.

The program consisted of a slideshow presentation of Glover’s illustrated books; a screening of No! You’re Wrong; a Q&A session, and a book signing. He only shows his films and slides during these live events, which means that very few people get to see them.

It would be in poor taste to reveal anything about No! You’re Wrong. Instead, I’ll talk about what happened after. On my way home, walking through the station at West Fourth, I noticed that a locker room for MTA workers was wide open. The room had a soft yellow glow, a few shades dimmer than the fluorescent tunnel, and no one else was around, which is strange in Manhattan. I thought I might’ve accidentally wandered onto a private level.

I held onto my confusion for a moment. My apartment is small and full of practical conveniences. The subway system is big and dangerous, at least in theory. If you catch it in an unusual moment, it’s good for the creative mind.

But I wasn’t in a secret zone. I made it on the same train I’d hoped to catch. I got back to my apartment at 10:30; washed my face; fed the cat. As I moved from the bathroom to the living room to the bedroom, I thought about the theater and the locker room, and why my apartment seems virtual when Crispin Glover, three paces from a row of mostly empty seats, is made of flesh and blood.

The next day I read about Sora, OpenAI’s new social media platform, where most of the content is AI-generated. A critic made the very good point that AI videos don’t place any demands on the imagination. They don’t take us anywhere. This is because they refer to nothing but themselves.

During the Q&A, I told Glover I’d like to see his other films, and he said he won’t release them digitally. He told me to sign up for his newsletter. I guess that means he’ll tour with them again.

He is filling the world with obstacles, and the obstacles are a frontispiece for what they’re obstructing. You have to get through them before you get to the goods.

These days there’s a lot of talk about how AI frees artists to be more creative. The idea is that manual labor and physical tools are superfluous to the creative process. In AI’s perfect world, making art is like dreaming: the work is fully realized as soon as it materializes in the brain. But dreaming is unintentional, and dreams tend to vanish from consciousness as swiftly as they arrive. The space between the conscious brain, the hand, and the heart is where real imaginative work happens.

That the three organs aren’t synchronized is not a flaw. Artists sweat over their disconnection, but it’s a healthy sweat. There’s a life force, a mana, in the strained conversation between these sites of production. This conversation creates reality within and beyond the body: the internal work that turns the self into a proper self; the work we undertake together to make form from chaos, planting seeds, building roofs. What fuels it isn’t separate from the artistic imagination.

Which is to say: imagination and reality need one another. It’s interesting to blur the lines between them, but we can’t do that if we think the lines don’t matter. This is what I would tell someone who didn’t know what to make of AI art.

A lot of artists grasp as much intuitively and choose low-tech tools, instruments that ask more of their minds. But I understand that for some aspects of creative labor, automation is a godsend. I don’t think there’s a grand unifying theory that explains how technology helps or hurts art.

If AI is making us dizzy, it’s probably because it doesn’t care about the difference between truth and fiction. I can still feel the earth under my feet (on some days more than others, admittedly), and I’m heartened by guys with 35mm cameras who preside over every encounter with their art, every flicker and gasp. Now and then, they take us from earth to heaven, and in the meantime they keep us looking up.

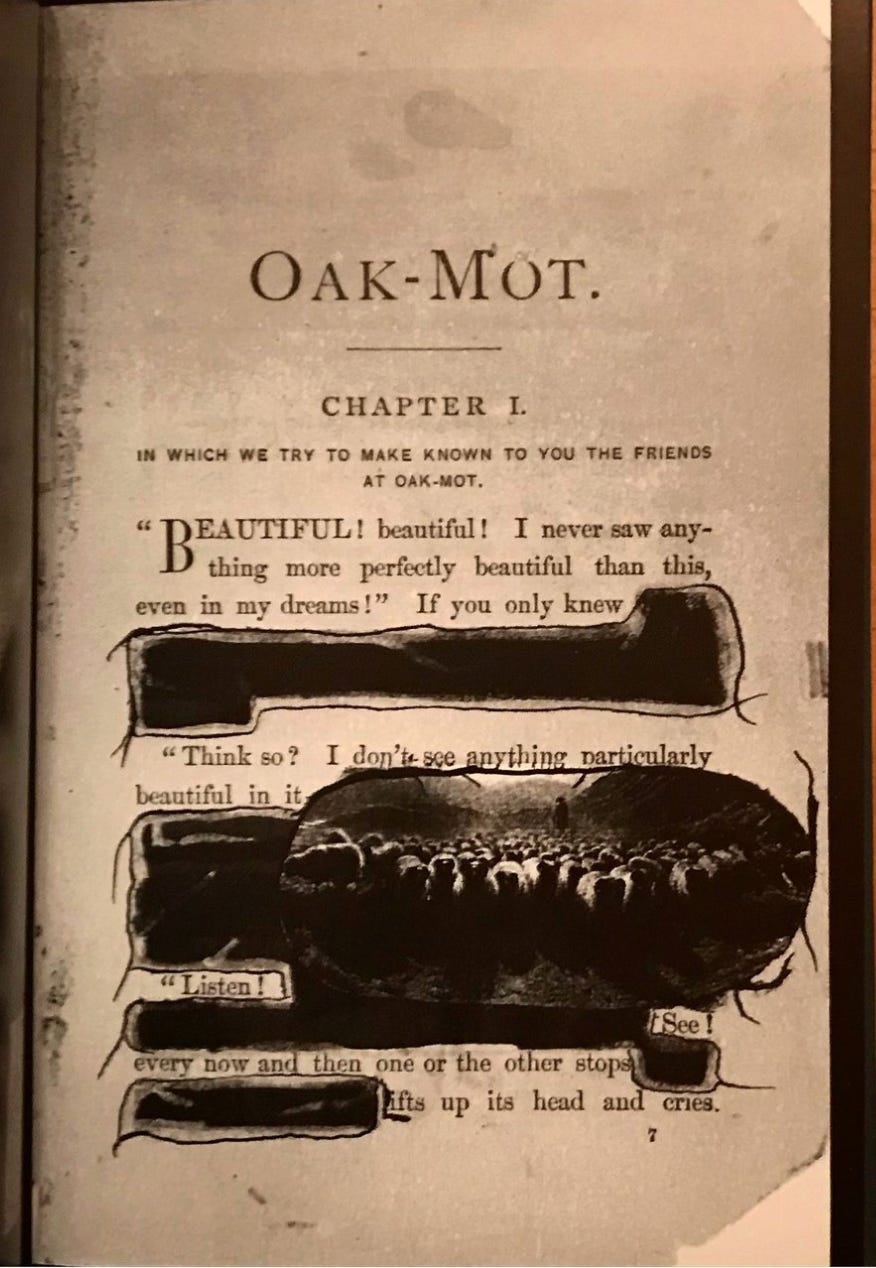

This approach to art (and wandering through subways with doors to incongruous light), that is, one of creating obstacles, is one that I am familiar with in my own practice. But I wonder what it says about the relationship of the artist to commerce if the extent with which one can be compensated and turn that art into things that nourish the body mind and soul, if those things are limited by physical distance. In one way it distinguishes it from the noise of a smooth online space of platforms but in the other it means the artist must already have enough attention that the audience can hear the shouts of "Listen!" and "See!" from their virtual corners.