The other day, I was talking to someone about Bloom’s taxonomy, a framework that teachers use to come up with learning objectives for their classes. My last job required me to include such descriptions on all of my syllabi: expected weekly outcomes, a few sentences each, featuring at least two “key verbs” from the taxonomy’s upper tiers.

This requirement did more harm than good. In class, I found myself having to fabricate connections between what was indicated on the syllabus and what we were actually doing that day, since I couldn't always fit them together. It was also demoralizing. Like most of my colleagues, I’d come up in a competitive academic job market where teaching chops are paramount. We would've liked to have been trusted to oversee our own course materials.

Since I’m no longer teaching, I have the time to think about teaching. One of my main gripes with higher ed today is that we assume students can and should develop the skills associated with the taxonomy’s highest level — the “create” tier, whose keywords include “formulate,” “build,” invent,” “derive,” and “generate” — in all courses, regardless of subject or level. The premium we place on ingenuity has come at the cost of instilling foundational knowledge. This is part and parcel of a society that treats the capacity for invention as an absolute value while deep understanding is increasingly discounted.

But my problem with Bloom’s taxonomy isn’t how it participates in a society based on relentless innovation. To treat the capacities associated with the “create” tier as universal goals for education is to normalize a highly dubious premise. This is that the structure, with its rote delineations between different types of activities, makes sense in the first place. If you’re defending a theoretical point in a humanities class, you’re probably developing an argument. In doing so, you'd be conflating verbs from tiers five and six. If you’re visualizing data, you’re illustrating it; those activities are in tiers three and four respectively. Data visualization also entails design and creation, both of which appear in tier six.

All models are wrong (they’re crude proxies for reality), but some are useful (they’re essential to scientific practice.) The thing is that blurry taxonomies, including but not limited to Bloom's, are a very special kind of wrong model. As irritating as it is to be forced to use them in your professional life, it’s worse to live in a world shaped by them. Their deposition in AI leads to countless social ills.

I’ll give some technical background for this point. The data used to train AI is known as the training set. Often these data contain “ground truths,” or labels that make up a model’s initial knowledge base (e.g., pictures of cats will be labeled “cat.”) After a model is trained, it’s tested on different data that also feature ground truths. These data generally do not conform to the strict rules of biological taxonomies, but they function as taxonomies in the same way that Bloom’s does: they help us recognize the difference between different sorts of things, so that a program knows a cat isn’t a dog, and a professor knows that “generate” is different from “illustrate.”

Some AI datasets resemble traditional taxonomic structures; many do not. (In all likelihood, relatively few do, but there’s no way to know for sure.) Sometimes data are fed directly into algorithms without any labels at all. In these cases, the AI’s job is to come up with them on its own. The classification systems that emerge from this process do not look like man-made taxonomies, but I still think of them as blurry taxonomies, because that framing is helpful for understanding AI’s core epistemic problem.

To explain what I mean by that, I have to cover the basics of biological taxonomies. In biology, taxonomies are standardized classification systems. They’re used to assign identities to specimens, so that you recognize this particular thing as “animal”; “mammal”; “carnivore”; “canid”; “domesticated dog.” Each declension inherits the properties its precedents, which is why I didn’t write “and” between “canid” and “domesticated dog.” The “and” might wrongly suggest that as you proceed towards the lower levels, you add to rather than derive from the preceding level, whereas the opposite is true — the higher levels are more generic.

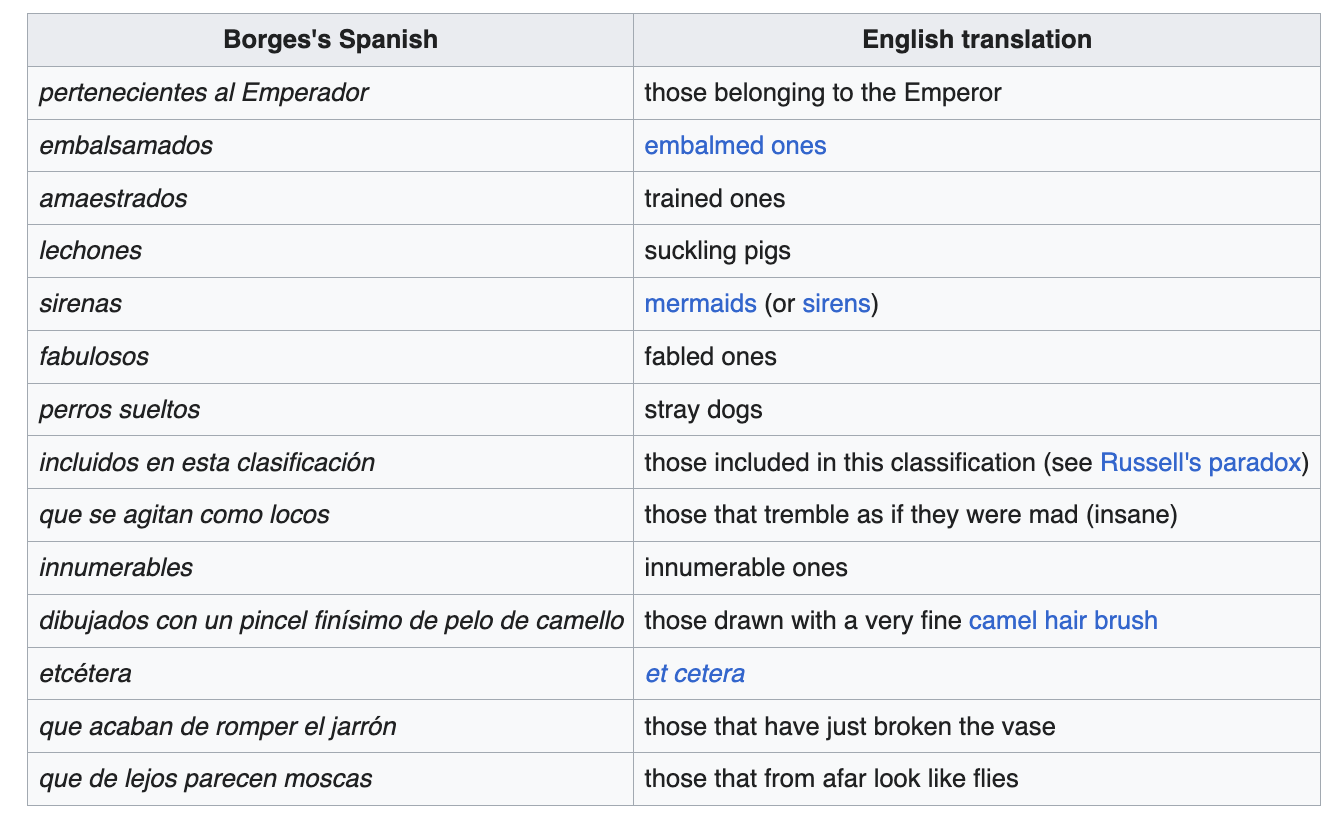

Divisions within each level are supposed to be mutually exclusive. One cannot be both plant and animal, vertebrate and mollusk, cat and dog. Biologists recognize the approximate nature of such distinctions (all models are wrong, etc.), but the mutual exclusivity clause is key. Without it, you might end up with a version of the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, a blurry taxonomy created by Jorge Luis Borges for his essay “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins." Here’s how Wikipedia depicts it:

The idea Borges was driving at is that the Celestial Emporium isn’t a taxonomy at all. It can’t be, as it’s riven with paradoxes, including the ultimate paradox of solipsistic enclosure, or closed-loop self-referentiality — the category “those included in this classification.” The Emporium’s structure has so little integrity that it’s practically nonexistent.

Biological taxonomies, which observe the mutual exclusivity clause howsoever tightly or loosely, and The Celestial Emporium, which draws this clause into high relief by way of negation, fall on opposite ends of a spectrum. As a particular taxonomy (e.g., Bloom’s) gets further away from biology’s side of the spectrum, its status as a taxonomy is increasingly imperiled. To some degree, this is a matter of individual judgment. I don’t see Bloom’s taxonomy as a taxonomy at all, but I know others do. (This was part of my conversation the other day — yes, I’m a lot of fun.)

Regardless of individual perspective, at least one element of taxonomic logic runs through all bodies of knowledge and might therefore be taken as sufficient for warranting the “taxonomy” designation. All definitive bodies of knowledge — everything we’d refer to as “knowledge” in the usual sense — come with conditional constraints. This means that we can qualify specific bits of data, information, semantic matter — whatever grouping of numbers, letters, or symbols we're calling “knowledge” — as either meeting or failing to meet criteria that would qualify them for inclusion or exclusion in one body of knowledge or another. In almost every case, these constraints are upstream of criteria that can be used to determine quality. “2+2=5” belongs to a body of knowledge called math, and using certain standards for evaluation, we can say that its quality is poor.

Even the “postmodern” subject areas come with standards for evaluation. It’s just that these standards tend to be arcane, and the contexts in which they obtain rather narrow and exclusionary. There’s a difference between writing a Derridean essay and writing a Celestially Benevolent taxonomy. (This is a tangent I feel strongly inclined to include.)

AI does not have such constraints. Regardless of the sort of element we’re taking as the bearer of knowledge in an AI system — say, a token or a model weight — it can be altered without the binding effects of what human beings recognize as the contours of a body of knowledge, that is, a corpus that coheres to the degree that it doesn’t abide too many internal conflations or paradoxes.

More importantly, it will be altered in this sense. The whole point of AI is that it assimilates everything it encounters, taking on a new shape in the course of doing so. Even with "safety" and "ethics" constraints in place, AI observes no universal distinctions, such as those that make sure “cat” and “dog” are always treated as mutually exclusive, or that “hand” always entails five fingers. And just as it fails to recognize any unbreakable lines within the structures that constitute it, AI acknowledges no boundary between the information that constitutes it — its “self” — and information that does not — an “other.” This makes it comparable to the Celestial Emporium’s “included in this classification” category.

Without stable internal and external delineations, without unbreakable principles, AI systems are infinitely pervertible: able to disintegrate into senselessness, unreason, without end. AI is nothing if not corruptible.

In my last post, I discussed psychedelic fascism. The psychedelic fascism of Blas Paul Reko and Julius Evola may appear to be quite different from the psychedelic fascism described by Stanley Kubrick many years ago — the “eye-popping, multimedia, quadrasonic, drug-oriented conditioning of human beings by other beings." As Kubrick suggests, one does not need drugs to be subject to so much madness. But if we believe that the deterritorializing effects of psychedelics are tied to Reko and Evola’s political project, the two articulations are compatible. When the machines that govern our lives acknowledge nothing integral in the conceptualizations we use to think clearly and communicate, when they can derange without end, we’re living under psychedelic fascist rule. This is the same thing as nihilist rule. Fascism's ultimate project, the politics of meaninglessness, the black pill.

I’ll wrap this up with a corny metaphor (I am a teacher at heart.) If you don’t see the beauty in the differences between colors — if you only wish for a world where they can be assimilated without end — you’ll wind up with no color at all.

This puts me in mind of what Geoffrey Hill called “plutocratic anarchy”, or the social and epistemic derangement wrought by the rule of money.

I think part of what Ben Noys was getting at in his critique of “affirmationism” (later, “accelerationism”) in The Persistence of the Negative is that systems without negation, without the principle that X entails not-Y, represent themselves philosophically as affirming a sort of abstract puissance - performativity, effectiveness, the ability to make stuff happen - which overruns taxonomies, territorial distinctions, binary oppositions and so on. But this puissance cashes out as pouvoir, coercive force majeure, the ability to rule opposition out of bounds. It can’t endure negation so it organises to crush whatever resists it.

Psychedelic fascism has something of that flavour to it. It’s all rainbows, permission structures, euphoric affirmation, until something or someone says no.