Psychedelic science has always had far-right elements. Albert Hoffman, who discovered and popularized LSD after a lab accident in 1943, was friendly with Ernst Jünger, a German nationalist known for having deeply equivocal politics. Jünger’s acid phase was a decade after Blas Paul Reko made the first scientific collection of Teonanácatl, a form of psilocybin used by the ancient Aztecs. Unlike Jünger, Reko was an avowed Nazi, as well as a scrupulous botanist. In a dissertation drawn from his cousin’s plagiarized work, Viktor Reko writes “The greatest toxic potency is always demonstrated by those intoxicating agents which are nationally and racially alien,” which is as solid an example of racist pseudoscience as any. Then there’s Julius Evola, the Italian fascist, mystic, and self-styled psychonaut whose book Revolt Against the Modern World has been praised by the likes of Steve Bannon and Richard Spencer, not to mention legions of extremely online conservatives. If the shroom-loving QAnon shaman didn’t read it, he probably read about it.

These links have gotten some attention in recent years. If the current psychedelic revival started with a whitewashed image of the golden era — the period of vigorous exploration and discovery that followed Hoffman’s fateful mistake and wound down around 1970 — its more critical proponents have taken it upon themselves to correct this misconception, highlighting the racist, sexist, and colonialist assumptions of some of its most influential projects. This push towards greater historical accuracy has led to the excavation and dissemination of documents proving that Nazis, conversion therapy advocates, etc., not only used these drugs but saw them as supplementary to their beliefs. Sometimes LSD opens you to otherness; sometimes it makes you more like yourself. Both carry risks.

Now that this history is out in the open, I want to connect right-wing psychedelia with reactionary modernism, a tradition of political thought first described by Jeffrey Herf in his 1984 book Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich. As John Ganz wrote in 2023, reactionary modernism is undergoing a renaissance thanks to the discourse-shaping influence of Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, and other members of the Silicon Valley intellectual set. Herf’s account of shared tendencies among thinkers like Jünger, Otto Spengler, and Carl Schmitt reveals a sensibility at once futuristic and illiberal, concrete and spiritual. In Herf’s portrayal, reactionary modernists saw disruptive innovation as a means to purify national identity and shore up individual autonomy, which would in turn ward off specters of social progress. They located real progress in technologization, believing that the goal of society was to serve technological aims, rather than the other way around. As Ganz writes: “Technology in the service of a hierarchical society and authoritarian politics, or rather, hierarchical society and authoritarian politics in the service of technology, as the correct pathway to unfettered progress and development.” This sounds like a fair description of where we’re at now.

There’s a sense in which medicine is always technological. This is especially true if you think there’s no principled difference between “technologies“ and “tools,” where the latter is understood to encompass any object that serves an instrumental purpose. Psychedelics are technological in this sense: if the studies are true, they’re means towards relief from a wide array of problems, including but not limited to alcoholism, anorexia, cluster headaches, and depression. If so much practical purpose isn’t enough to grant them the “technology” designation, you might consider the spoils of today’s overtly digital brand of psychedelic medicine, which includes advanced neurotech, tripping apps, and VR programs designed to simulate the effects of hallucinogens. This is the context in which Robin Carhart-Harris, arguably the most famous psychedelic researcher alive today, proposed a highly influential grand unifying theory of psychedelic activity based on machine learning frameworks. Assuming this sort of research will continue apace, psychedelics are becoming more and more concretely technological as time goes on.

But the psychedelic science-reactionary modernism link doesn’t reduce to their respective associations with tech, which are both scientific (as described above) and cultural (through their shared global locus, the Bay Area). If that were the case, one could just as easily tie effective altruism to reactionary modernism, and I don’t see that connection holding up under scrutiny. Psychedelic science warrants examination through a reactionary modernist lens first and foremost because of its particular epistemological commitments. Specifically, it’s a form of science that clearly bridges the “soft,” or psychological, and “hard,” or biophysical, but whose dominant agendas notably favor the latter. Carhart-Harris’s thesis is that these drugs bypass reflexive mechanisms and break down abstract representations of the self — the internal patterns by which selfhood coheres, that make it, for all intents and purposes, real — in a causal chain that closely follows the logic of progress-through-disruption, or healing-through-death (ego death, that is). This may all sound rather psychological, but it’s borne out by data from empirical neuroimaging studies and quantitative analyses. These studies have no water without subjective testimonies from human beings, but that dimension is persistently downplayed. The conscious labor of abstraction — which includes self-aware reflection and analysis — plays at best a peripheral role in psychedelic science’s most visible configurations.

Reactionary modernism is suspicious of the abstract, in both its noun and verb forms. As Ganz points out, the movement attributes the productive function of abstraction to a decidedly Jewish (“parasitic, financialized”) form of capital, while technology represents capital’s more “positive, concrete, [and] productive” dimensions. In his words, reactionary modernists oppose “Jewish” merchants, like the Soroses, with paragons of whiteness à la Thiel and Musk. In this dichotomy, technology stands for a romantic and anti-semitic “anti-capitalism” that’s only anti-capitalist to the degree that it resists the alienating effects of information exchange and other artifacts of globalized, abstract labor. These are the artifacts that forms the basis of Evola’s “modern world” — the future whose emergence the Third Reich tried and failed to foreclose.

Ganz continues with a reading of Moishe Postone, who identifies the origins of the concrete labor-abstract labor dichotomy in Marx’s famous distinction between use-value and exchange-value. The former is on the “romantic” side; work that takes place under its sign appears as “a purely material, creative process” that belongs to the domain of the “natural” or artisanal rather than anything “unnatural,” or Jewish. Ganz quotes Postone as follows: “the former appears ‘organically rooted,’ the latter does not… in this sense, the biological interpretation, which opposes the concrete dimension (of capitalism) as ‘natural’ and ‘healthy’ to ‘capitalism’ (as perceived), does not stand in contradiction to a glorification of industrial capital and technology. Both are on the ‘thingly’ side of the antinomy.”

Psychedelic science’s search for biophysical rather than psychological healing mechanisms tracks with reactionary modernism’s definitive attachment to “thingliness.” As so many researchers see it, psychedelics activate an “innate healing capacity” that’s principally of the body rather than the mind. The mind, which has the unfortunate habit of turning towards the conceptual, is broadly implied to be the problem, and often explicitly illustrated as such. It’s identified with an ego that needs to be cauterized in order to allow something newer, stronger, realer to emerge in its place. A mysterious force that lies, perhaps, beyond the remit of what can be rendered as information.

Epistemology is the main thing. Psychedelic science is reactionary as it strongly prefers the “hard” over the “soft.” This orientation makes sense to some degree, as researchers necessarily deal with molecules and carrier mechanisms. Eduardo Schenberg writes of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, one among many proposed models for standardized psychedelic treatment, as a "paradigm shift" due to this exact particularity. PAP bridges “hard” psychiatric interventions with considerations not only for the psyche, but also social determinants of well-being. His vision of psychedelic medicine suggests that the heavy emphasis on neuroscience over psychology, on the objective over the subjective, is not the only way.

The cultural components bear some mention. Psychedelic science inherits affective and moral ties to the hippie movement, which has its own reactionary streak (think back-to-the-land projects; the rejection of modern medicine; the romantic objectification of nature). As a non-hippie who can’t help but see these tendencies as aesthetic reductions of the political, I’ve often felt I was a bit too dyspeptic, too thinky, to call the field my own. I suspect I’m not alone there.

This is a very general depiction. A number of scholars are committed to advancing psychology-forward psychedelic medicine. I’m scrutinizing the field as it’s conceived on the world stage, and I’ll admit that it’s been a few years since I’ve been to a psychedelic conference. If my grasp of where things are these days is off, I’d be interested to know.

I’ve been meaning to write something like this for a while. I got the idea for it at the same time that I presented a paper called “Psychedelic Fascism in the Digital Age” at the 2024 California Ideology Conference. This post is based on notes dating to early that year. A more complete account of the psychedelic science-reactionary modernism link would focus on specific actors, agendas, and, in particular, funding sources. If I were still in academia, I might have the resources to work on such a project. For now, it’s probably off the table.

I am not a scientist. My background is in STS. My job used to involve talking about the social contexts of science and technology, context that others might miss. Psychedelic science doesn’t need this treatment nearly as much as, say, AI. But the most insidious versions of right-wing tyranny necessarily get less attention than whatever Trump is up to, and I’m supposedly qualified to call them out, and I wrote a dissertation about psychedelics. I’m here to do something specific.

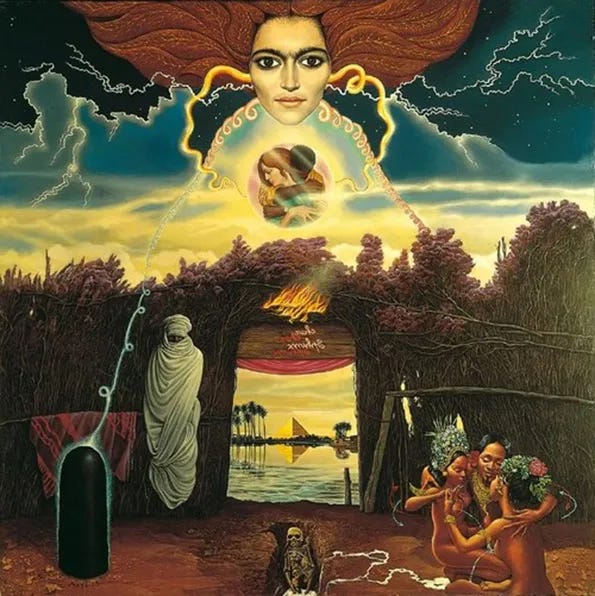

Fascism can look and feel awfully trippy. It can inhibit clear thinking about the politics of what appears to be ideologically neutral on the surface. Please watch out, lest your senses get deranged.

I don't have my finger on the pulse of contemporary psychedelia, but I know a bit about the post-1960s ideas of Leary and McKenna. Glancing at your thesis, I don't find them mentioned anywhere, and I only see one reference to the deep state's interest e.g. in LSD. But I do see Shulgin and Erowid mentioned. Are hippie spawn and the spy world anywhere in your genealogy of the new psychedelic advocacy, or is it all born from the online communities of the 1990s? I'm sure Joe Rogan has referenced McKenna's machine elves...